Playing With Baby

Charming vintage drawing by Walter Crane of two older siblings playing with baby on the hearth rug. It dates back to 1887.

A collection of over 4,755 free downloadable public domain images for crafters and web designers that have been rescued from old books, magazines, and other print materials. All of the images in this collection are copyright free in the United States and any country that extends copyrights up to 70 years after the death of the original artist making them in the public domain and free to use in your next scrapbook page, notecard or other craft projects.

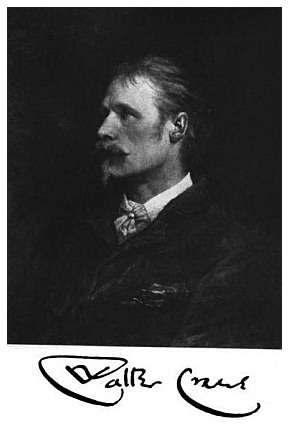

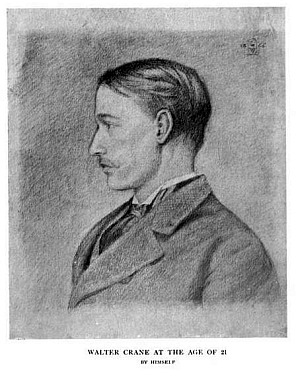

The art of Walter Crane (1845-1915) runs the gamut from fine art paintings to caricatures and other humorous pieces. He also designed ceramic tiles and wallpaper. Here on Reusable Art, there are primarily examples of his wonderful illustrations that were used in children’s books. He was one of the most influential English artists during his time or for generations to come. His name is often paired with Kate Greenaway and Randolph Caldecott as being three of the driving forces for the direction nursery book illustrations would take as color became affordable.

Prior to writing about Walter Crane, I had decided that I would not write about what school of art influenced his work or focus heavily on listing the multitude of works known to come from his talented hands. I looked at Wikipedia and a number of other websites including a number provided by academic institutions and was left wondering about the man behind the pen so to speak.

Thanks to Google Books, I found An Artist’s Reminiscences which was written by Crane about his life and early influences. I wouldn’t know a pre-Raphaelite work from a post-Raphaelite work, assuming there even is such a thing. But I find Crane’s illustrations very distinctive and recognizable from my work with them on here on Reusable Art. I have no idea how long Crane’s own words have been online, but it was interesting to discover that even some of the more reputable sources had facts incorrectly stated when compared to Reminiscences.

Thanks to Google Books, I found An Artist’s Reminiscences which was written by Crane about his life and early influences. I wouldn’t know a pre-Raphaelite work from a post-Raphaelite work, assuming there even is such a thing. But I find Crane’s illustrations very distinctive and recognizable from my work with them on here on Reusable Art. I have no idea how long Crane’s own words have been online, but it was interesting to discover that even some of the more reputable sources had facts incorrectly stated when compared to Reminiscences.

So, rather than talk about specifics about his art and the particular artists and styles who influenced his work, I thought it would be more interesting to talk about his early life and learn more about Crane the person than Crane the artist. Reminiscences tells of boyish mishaps, his first commission and a variety of aspects of his life not mentioned elsewhere.

As Crane comments, “Life is a strange masquerade: as the procession passes in the glare of the full noontide one hardly grasps its full significance, but perchance partly lost in the mist of the past, one becomes aware of larger meanings, and in perspective both persons and events assume different proportions.”

It was perhaps somehow meant to be that Walter Crane would come to be a book illustrator. His grandfather, Thomas Crane was a bookseller and editor of the Chester Courant. Walter’s father and his three brothers, William, John and Philip ran a lithographic press. His father was a well-regarded portrait artist and completed several portraits for members of the realm including the Duke of Westminster. Additionally, Walter wrote in his autobiography that he suspected he was also related to the great tapestry artist who lived during the reign of James I in the early 1600s – Sir Francis Crane.

After two of his uncles immigrated to Australia, Walter Crane’s parents moved to Liverpool where his father became Secretary and Treasurer of the Liverpool Academy of Art. Walter was born on August the 15th 1845. He remarked that was the same calendar day as the death of Napoleon the First and the birthday of Sir Walter Scott.

Walter was only three months old when the family was forced to leave Liverpool and move to Torquay, due to his father’s poor health and presumed case of consumption. They later moved to the Devonshire village of Upton where Walter recalls some of his earliest influences on his art.

In 1851, Walter Crane and his siblings would “experiment in colour” with pictures from the Illustrated London News of the great Exhibition of 1851 in London. John Gilbert’s (1817-1897) work in children’s story-books, Goldsmith’s Natural History and Animated Nature and other children’s publications were among the earliest pictorial influences on young Walter outside of his own father’s work; which at the time was primarily portraiture.

Walter speaks of early memories of his father working in his studio, drawing his own hands to prepare for his full and half-length portraits. His father, when done, would cast aside these studies where they would often lay on the floor, Walter’s “drawing table at that early period.”

Walter speaks of early memories of his father working in his studio, drawing his own hands to prepare for his full and half-length portraits. His father, when done, would cast aside these studies where they would often lay on the floor, Walter’s “drawing table at that early period.”

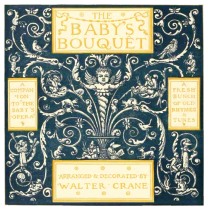

The younger Crane would then draw fancy portraits of gentleman attached to the hands. Walter often focused more on the decorative aspects of portraiture – often “fancy waistcoats” in large floral or tartan designs. His decorative work often led to the people becoming out of perspective. But, even with my untrained art knowledge, I would suspect this was truly the beginning of his distinctive style. Like the book cover shown here, there’s extra details everywhere. The full-sized version of which is available here – Four Picture Frame.

When his father’s sketching club would meet at the Crane household, young Walter’s efforts were encouraged by a number of professional artists of the time. Throughout childhood, Walter was rarely seen without a pencil or slate and was often referred to by one neighbor as “The Little Artist”.

However, like most little boys, Walter, had a few troublesome moments that were far less artistic. Perhaps inspired by the Crimean War, there was a close encounter with gun powder that led to missing eyebrows and eyelashes after a backyard battle with his younger brother. Another boyhood adventure had him standing upon a side-table to check out his battle attire in a pier glass mounted in the mantelpiece. He might have looked good but the “alarming splash of ink upon the creamy-coloured field of the Brussels carpet” did not.

In his autobiography, An Artist’s Remembrances, Walter Crane wrote of what could only be called a life full of images of world and personal events full of potential to influence his art. Gypsies, wild-beast shows, climbing and exploring large sailing ships, posing for early daguerreotype pictures, sailing regattas, butterfly collecting and a whole host of activities Crane talked of later in life with fondness.

Early access to the works of several masters as well as a lecture on hieroglyphics further cemented the direction young Crane would take in life.

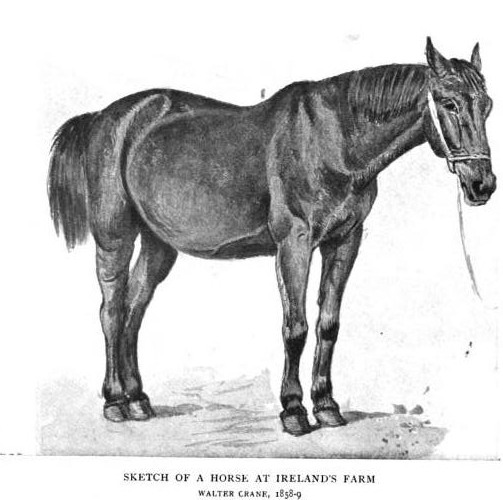

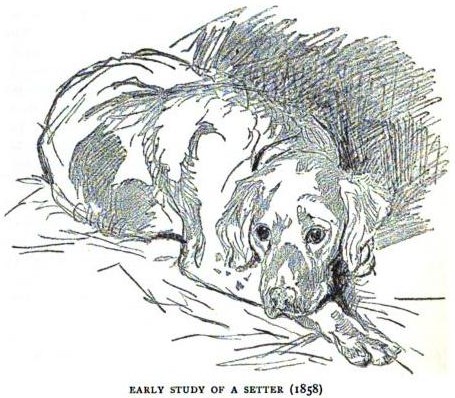

When the family moved to London, it provided young Walter with the ability to explore The National Gallery and become exposed to even more artistic influences. While his father was known to paint landscapes and experiment in other art forms, he was most well-known as a portrait artist. Walter, on the other hand favored animals and nature.

When the family moved to London, it provided young Walter with the ability to explore The National Gallery and become exposed to even more artistic influences. While his father was known to paint landscapes and experiment in other art forms, he was most well-known as a portrait artist. Walter, on the other hand favored animals and nature.

While in his teens he sold a work called “The Donkeys” for “the magnificent sum of 10 shillings”. Walter painted it from another artist’s work to learn the other artist’s technique. The Donkeys was not one of his personal favorites, as he preferred to draw direct from nature or his own head.

Walter’s first essay in oil-painting was under his father’s direction and was of a black and white grey-hound’s head.

His first commissioned piece was actually paid for in the form of a glass of milk and further access to his model. After being caught at Bedford Park sketching an “old shaggy pony”, its owner, the milkman, offered the commission and access his property where that pony and “other interesting animals” lived. The two illustrations shown were also drawn by Crane during this time.

Around that time, visits to the South Kensington Museum provided access to even more artistic forms which further rounded out his early art education.

Walter often amused himself by illustrating poems that he was fond of.

The illustrations were often in the form of small pen sketches. Tennyson’s poem, “The Lady of Shalott” must have greatly inspired Walter for he developed a complete set of pages in color for Tennyson’s work. Each page contained a “subject enclosed in a sort of border with text written within it.” It was, at the time, young Crane’s most complete work to date. As the work passed among friends, it came to the attention of W. J. Linton, who was perhaps the leading wood-engraver at that time as well as a writer and poet.

Upon seeing Crane’s work, Linton offered him a full apprenticeship without the usual premium. For Linton, it was not the colors of the work but rather the potential for Crane to become a designer that interested Linton in his new young protégé. In January 1859, Crane signed and sealed into an indenture of apprenticeship for three years. Years later, Crane still recalled the solemn words of the oath he said upon the agreement, “I deliver this as my act and deed.”

It was during this time that designs were drawn upon boxwood and engraved to form the plates from which books would be illustrated. Crane’s early work for Linton included making little drawings for the apprentice woodcarvers to practice on. When the boxwood blocks were cut for full-page wood prints, the outside edges of the tree were used up in this manner. I would suspect many of these little drawings were often used for drop cap letters, page spacers and borders so common in printed works from this period.

It must have been an interesting time to work in the making of printed materials as changes in the way the cuts were made allowed for greater speed and detail. What was once previously a single block worked on by one engraver was now a virtual jigsaw puzzle of components assigned based on skill with the faces being given to the most skilled and experienced carvers.

In his off hours, Crane continued his work in other mediums and undertook at least one commissioned portrait. During his tenure with Linton, Crane worked on such things as a series of bedpost images for an advertising catalog (something he later did not remember fondly), zoological images, and as a “special artist” documenting cases at the Law Courts in Westminster Hall and other public events for newspapers. Visiting the zoo allowed Crane to meet many other artists of the time who were both established artists like J.W. Wolf and contemporaries on their way to success like Ernest Griset.

In the summer of 1860, a year after his father’s death, a favorite uncle invited the family to Littlehampton, near the sea. Crane mentioned a heavy paper duty, “imposed by some wiseacre’ which led to the creative use of his uncle’s old pattern cards with the cloth samples removed to sketch upon. His uncle made his living selling cloth and the pattern cards were typically disposed of once the patterns were no longer being sold.

After finishing his apprenticeship with Linton in 1862, Crane saw some “bits of original work” published in the small monthly journal “Entertaining Things” which is perhaps better known for containing one or two of the earliest drawings by George du Maurier. Crane struggled to find work after leaving Linton and relied upon friends and acquaintances for work as well as introductions.

One of his earliest jobs was to make some drawings for an Encyclopedia. Due to his youth, Crane had to obtain a special endorsement in order to obtain a ticket to enter the British Museum Reading Room. Access to the great library gave Crane the opportunity to draw a variety of subjects.

Crane sold several pieces related to “smart resorts” such as Richmond Hill and illustrated several other works for the new London Society magazine including the various dog characters depicted in Charles Dickens’s novels.

Crane gave much detail as to the different people and periodicals he worked for in those early years and to some extent they include a virtual who’s who of British literature, culture and thought of that time.

It wasn’t until 1865, at only twenty years of age, that Crane began doing the work which would make him a treasured artist for generations to come. That year he began to design for Edmund Evans, a pioneer in the development of color-printing, and the children’s picture-books published by the house of George Routledge & Sons.

It wasn’t until 1865, at only twenty years of age, that Crane began doing the work which would make him a treasured artist for generations to come. That year he began to design for Edmund Evans, a pioneer in the development of color-printing, and the children’s picture-books published by the house of George Routledge & Sons.

Prior to the Routledge work, Crane illustrated several works for Messrs. Warne including a History of Cock Robin and Jenny Wren, Dame Trot and her Comical Cat and The House that Jack Built.

Crane met the lady whom would become his wife in 1868. She spent the winter traveling while Crane wrote “inscribing sonnets to the absent beloved one.” Their wedding was further delayed when she became ill during the sixth month of their engagement in 1870.

Finally, September 6, 1871 was set for their wedding day. Crane tells of obtaining “that priceless and momentous document, a marriage license” and an exciting wedding day. Somewhere in London, one of the horses pulling their brougham fell and garnered the attention of a large crowd, many of whom helped to get the horse up but then presented themselves at the carriage window for tips. After a honeymoon touring Europe, making stops to pay their respects to the monuments of Gutenburg and Schiller and many of the other great treasures of the art world; the couple returned to England in May of 1872.

So, for now, I’ll leave Crane and his new wife. By this time he was becoming quite well known for his children’s illustrations. He still could not get the Royal Academy to accept one of his works but I’ll leave it to you to find out if they learned the error of their ways during Crane’s lifetime. If you are interested in truly learning more about what inspired this wonderful artist, do seek out his book and hear it from his own words rather than mine or some “expert” or “authority”. The book is quite an interesting read as it tells something about life during that time as well as the many changes in book publishing and printing that took place during Crane’s life.

Along with the wonderful book illustrations, Crane worked in water colors and oils as well as designed wall papers for over 30 years and at least one set of Christmas cards and another of valentines. Walter Crane died on March 14, 1915 leaving behind a virtual library full of beautiful art.

Two of my favorite Walter Crane Illustrations from Reusable Art are Children at the Beach and Sir Dan de Lion.

|

|

|||

Playing With BabyCharming vintage drawing by Walter Crane of two older siblings playing with baby on the hearth rug. It dates back to 1887. |

Baby in HighchairWhat a fun image Walter Crane has given us in this vintage drawing of a baby in a highchair. The boy sits with his foot on the table and his hands full. |

Umbrella MishapA charming piece by Walter Crane with a poor little girl in the middle of an umbrella mishap. Don’t you just want to reach out and help her up? I do. |

Japanese Rabbit WatercolorPublic domain Japanese rabbit watercolor. Done with a large, soft brush and black ink by Walter Crane it offers a charming image to use in your own work. |

Chicken ScratchIt looks like it was constructed a bit like the scene it depicts – chicken scratch. It was drawn by the prolific children’s book illustrator Walter Crane (1845–1915). |

Peacock DrawingPart of drawing lesson on creating different textures, this peacock drawing would make a great coloring image. |

|

|

Cherub with Art Palette DrawingRecognizably Walter Crane, this vintage image features a large art palette and brushes being held by a winged cherub. |

Apple VignetteDrawing of a trio of golden apples that would make a great page spacer or vignette. This apple vignette is available with red apples too on ReusableArt.com. |

Metaphor for TemptationGreat border/vignette image of someone handing over three apples along with a snake – a great metaphor for temptation. |

Frame with Boy & GirlVintage line drawing of a girl and boy holding a book that could be edited for your own text. |

| ~~~ | |||